When I think of these kinds of stories, movies like Mad Max, 12 Monkeys, or even Zombieland come to mind, all set around the modern day. For this setting, I've been thinking about how the usual post-apocalyptic tropes can apply to an earlier era.

Reclaimed by nature

With so many people dead, the wilderness is full of ruins: forts and villages and mines that were once maintained by people, but have now fallen to the forest. Abandoned sites have layers of history, even in the short time since the apocalypse. You can see why they were built, how they fared in the end, how the forest has grown over them, and even who's been there since.

|

| Overgrown Tomb, Steven Belledin |

Ruins aren't clean, static places; they're as changing as the forest. Rain gets in, flooding and rotting. A wall becomes home to bees. Tree goblins nest in the rafters. A cellar holds a sleeping bear. Floors crumble and rot through, stairs fall apart, and the site gradually fades away into the forest.

You'd have to be pretty desperate to try to make a living on scavenging from the ruins. But most adventurers are desperate, in one way or another.

Raiders

Crops failed in the starving time. Tens of thousands left home in search of a chance at survival, anything to eat, anything better than where their neighbors died. When it's either you or them, someone dies and someone gets to eat for another day.

Those few who were better stocked with food found themselves the target of repeated attacks. In many cases, the walls held and the raiders starved or moved on. Others were not so lucky.

Over time, raiding and thieving became a way of life for many, an accepted means of supplementing your food supply in lean times. Out away from more prosperous parts, it's still a desperate world, full of people who have no qualms about robbing a stranger to feed their kids.

|

| Ambush at Lovewell Pond |

Meeting someone on the road is a wary affair. There's a decent chance they're here to rob you, or that you're here to rob them. Keep your hand on your pistol and assume every encounter is a trap.

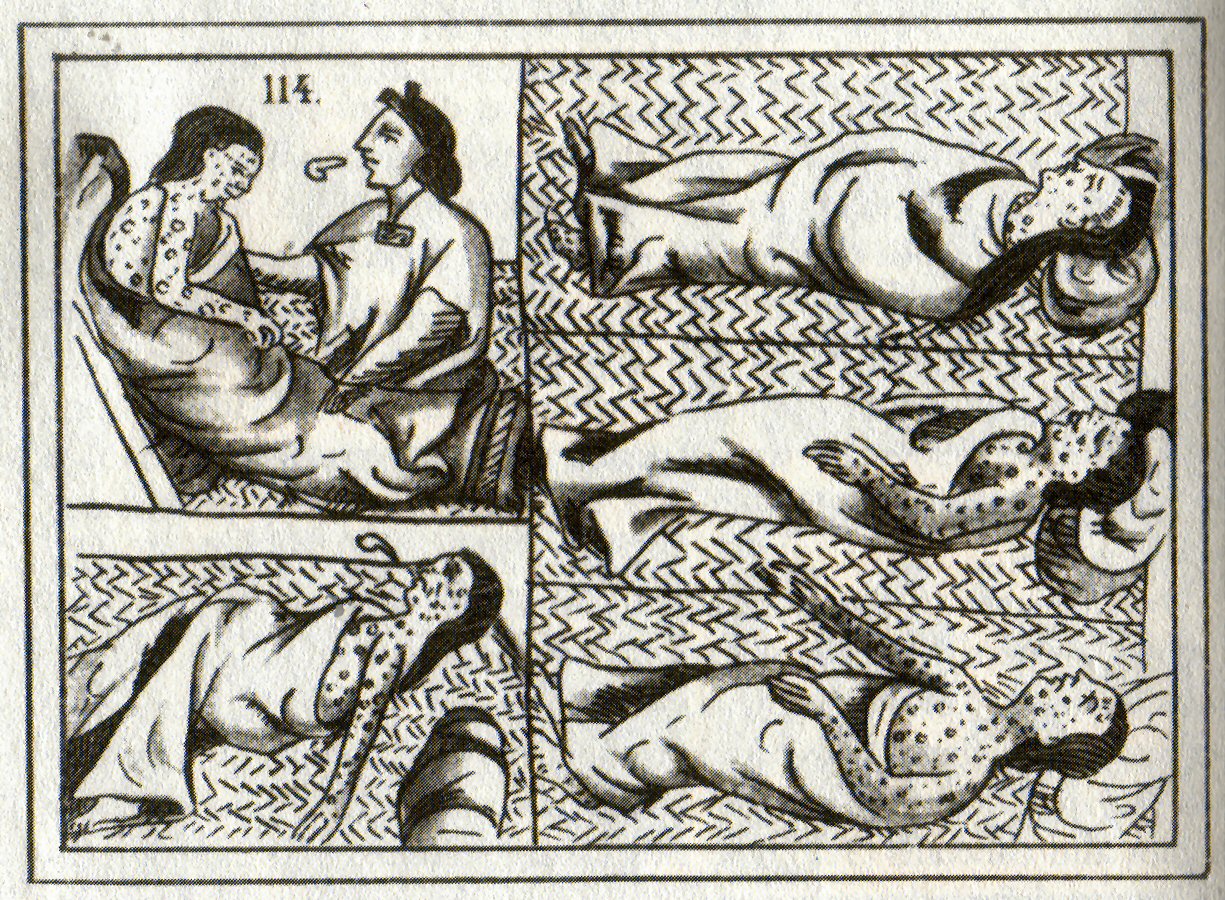

Everyday violence

This generation was raised by a broken and traumatized people. Their parents watched people starve in the streets, buried piles of bodies when the plague came, and did things to survive that they're not proud of. Brokenness begets brokenness, and their children learned hard lessons at a young age.

Rude words lead to a fistfight. Slight someone's honor and you might face them in a duel. Intrude on the quiet of a town and you might get a beating, but you might get hanged from the nearest tree.

|

| Duel with Cudgels, Francisco de Goya |

A party of adventurers is always in danger around other people. They're perpetual outsiders who can be blamed for all ills, strangers with no one to avenge them. To survive, they'll have to be ready for violence, which only makes isolated settlements even less likely to want them around.

Warlords

The cruel hand of fate didn't strike everyone evenly. Anyone with a good source of food and some decent weapons might find themselves much better off than their neighbors. That kind of power corrupts. You end up with petty warlords, ruling over a valley or two by doling out survival to those who fight for them.

Loyalty to the warlord means you get to eat. Defiance brings punitive raids. You can't fight for long once someone's burned down your barn, and with it all your corn for the winter.

|

| Powhatan, John Smith |

These days, every government or power structure operates a bit like a warlord. A company administrator hands out rations and beatings just as well as a tribal chief or an elected mayor. Traditions and pieces of paper don't bring power the way food and guns do.

For up-and-coming adventurers, this means hard choices. To get along, you're going to have to gain the favor of some bad people. The company might pay well, but they might send you to burn down a whole village. The council might keep you fed, but only as long as you bring them the heads of their rivals. And what happens when you're powerful enough that you don't need some warlord's support? How do you stay in charge without resorting to their cruelty?

Dirt and grime

Everything is broken and dirty. Someone comes stumbling into the tavern? You know they're covered in mud, soot, dust, blood, whatever. Every inn is a grimy little place. Every traveler looks a bit like the road they travel down.

|

| Couple in a Tavern, Todeschini |

But to make the griminess really stand out, a bit of contrast is in order. The spirit glass hanging outside the city is actually kept clean and sparkling. The boss takes a bath every night, and her guests eat a proper dinner from fine china. The telescope is wrapped in a clean, white cloth.

If you want to look rich, look shiny. Hot baths and clean clothes are a luxury few can afford.

Makeshift and repurposed

People are clever, especially when they don't have any better options. Old things that can't be made anymore are too valuable to throw away, so they get repurposed and made into other things.

Every settlement has something from the old days that's been repurposed. The inn used to be a grist mill. That spearhead used to be a drainpipe. The tank from the brewery is now a boat. They tore apart the ship and built it into their fortifications. That necklace is made of old doubloons.

|

| Zuni blacksmith shop |

Things have stories. Treasure in this world comes with complications: competing claims, malfunctioning parts, and unexpected benefits.

Earth-that-was

After a great collapse, people tell stories about the world that came before. The past is simplified and idealized, turned into a standard story to help you understand the way things are now.

Some people say it was a better time, venerating the ancestors and calling for a return to their way of life. Some say it was a decadent age, swept away in a great cleansing of the world.

|

| city of the Mound Builders |

Many are in mourning for the old world. Those few elders who lived in it wistfully think back on the days of their youth. Their children and grandchildren who grew up in the new days speak of the old as a lost age of glory that will never be attained again. Whole societies can go on for centuries mourning their golden age.

Relics from the olden days elicit mixed responses, from awe to disdain.

For this article, I've deliberately avoided mentioning some of the usual post-apocalyptic tropes about cars and ammunition. I think you can still get across most of that concept in a world of muskets and canoes.

I've got a few ideas for posts I'm working on. What would you like to see next?

- how people are changed by the frontier

- population dynamics of the elven hive

- prophets and preachers of new religions

- how humans are scary monsters

- newfangled inventions